Since the inception of COVE and the discussion we have created regarding the importance of visual literacy in seeing and interpreting the world around us, we have focused on how broad the application of visual literacy really is. When you think about it, there is very little we actually do if we are able sighted that doesn’t begin with looking. Too often we look past what has become familiar to us and we no longer see it. We allow various visual and personal biases to influence our interpretation of what we see and as a result, the actions that we then take. We have talked a lot about why this matters to hazard recognition, incident investigation, and other safety processes.

I am excited to share our involvement in a new project sponsored by the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) focused on how we can utilize visual literacy to improve hazard recognition in “design for safety” processes. EPRI’s Occupational Health and Safety Advisory Committee members identified hazard recognition as a priority research area and expressed interest in improving hazard recognition in design for safety practice using visual literacy. As EPRI highlighted, research shows that decisions made during project planning and design influence the safety of those who construct the design as well as those who maintain and operate the new facility/infrastructure after it is built. The better job we do at the design stage the safer the final product will be.

The intersection of visual literacy and design practices is relevant in many aspects. Visual literacy is all about what we see, what it means, and what action we take as a result. Everything is an image that requires interpretation so that we know what it means. This includes not only paintings, photographs, sculptures, and other forms of art but also work environments that are much more familiar to most of us. A piece of equipment, a production line, and a construction zone is every bit of an image as is a work of art. And these images require interpretation as well in order to ensure they are safe, productive, and fit for their intended purpose.

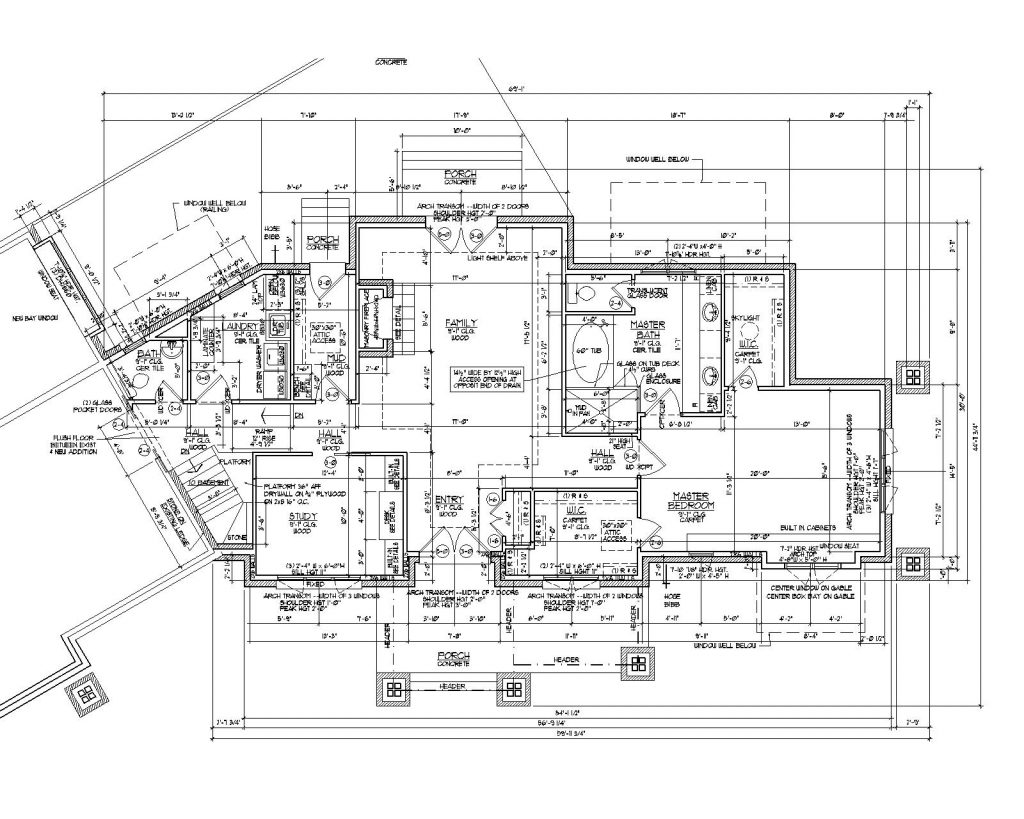

Design practices are filled with images as well. These include drawings, specifications, diagrams, examples of existing assets, etc. Each of these require interpretation and sometimes imagination in order to draw meaning from what we are engaging with. Failure to see the details can result in impractical designs, an unsafe working environment, and suboptimal outcomes. Addressed at the design stage, solutions are most cost effective and least disruptive. Scheduling may be improved by addressing staging and logistics issues in addition to improving safety during construction and operations. Addressed during or post construction or implementation, solutions are often disruptive and costly. Timelines may be extended, upsetting customers and other stakeholders. Worse yet, we live with them until there is time or money to correct them.

The better we understand how we all see and interpret images, the better we are able to ensure others will safely use, operate, or interface with the items we design. Understanding visual literacy can help influence engineers and designers’ choice of things like color, space, shapes, etc. in order to design out visual traps which could lead to hazardous exposures or behaviors by users and operators.

By its nature, visual literacy provides an opportunity for being proactive in our safety processes. If we are constantly responding to incidents that have occurred, our primary safety actions are by default looking backwards based on what has already happened. While necessary, this is a lousy way to proactively address safety improvement opportunities. No one wants to volunteer to be the next injury so we can learn the next thing we need to fix!

“Fatalities and serious incidents that occur in construction work can be directly linked to the level of prevention incorporated into the planning and design of the project.” [1 – Prevention Through Design by Bruce K. Lyon, Georgi Popov and Elyce Biddle. Professional Safety September 2016] We know this as well in our normal operating environments and it should be no surprise that if we do a poor job of identifying hazards and the corresponding risk in new projects and as a result, fail to mitigate them our opportunity for incidents increases. This may be perceived as more difficult since we have only drawings or computer generated images of what we are creating, the same principles associated with visual literacy apply.

If we lack a disciplined approach to reviewing drawings or imagery associated with a design project, we risk overlooking critical details that may be different from our experiences, our expectations, and our visual biases. While we believe that we see with our eyes, we are actually seeing with our brain. And the brain is knitting together images to form what appears to us to be a high definition “movie” of what we are looking at. In order to accomplish this amazing task, the brain must fill in the blanks so that it all makes sense to us. Unfortunately, we don’t always fill in the blanks accurately.

Think for a second of the email you may have written that included a misspelled word, a missing word, or something even more embarrassing even though we proofread it before we hit “send.” It is so easy to overlook something because it is familiar. We know what we meant to write and that is what we see. Our experiences and expectations guide our interpretation of the images we are looking at and if it is different from what we expect, we can misinterpret what we are seeing.

We can improve our ability to not just look at what is in front of us, but really see what is there. As a result, we can strengthen our interpretations of what we are seeing and reduce the risk that we will overlook a potential hazard in the construction or operation of the project we are examining. While sometimes unpopular to say, we must begin by slowing down and not leaping to conclusions about what we are seeing. “I have seen this schematic dozens of times and there is nothing here to be concerned with” can be the thought process and we may often be correct. But what if it is a bit different this time? Think of the proofreading example.

The application of the tools of visual literacy that we often discuss is relevant to live environments as it is to representations of environments that are yet to be created. We can utilize the Elements of Art to see lines, shapes, colors, space and even textures in any image including drawings and computer generated images as well as mockups in order to break down the image we are examining. We can utilize the Principles of Design to interpret flow and movement, as well as balance and symmetry. And rather than following a random and impulsive examination of the image, we can apply a disciplined approach to our eye movement across and around the image to assist in the completeness of what we see.

Think of no better example than “Where’s Waldo”. It is much easier to find Waldo when we structure our examination of the image with discipline – perhaps perimeter to interior – than if we scan and rescan the image randomly hoping to spot an indicator of where Waldo is.

Leveraging our experiences and applying them strategically is a powerful approach when recognized for what they are – looking backwards and determining their value in going forward. Understanding our data and where and why incidents have occurred in the past can provide valuable insight to the design for safety processes. There is no reason to repeat hazards that can be mitigated with some thought in the design process. We are again dependent on our ability to “see” them in the new designs.

The integration of visual literacy skills with design for safety practices offers the best of both worlds. Leveraging best practices, standards, checklists, and design processes well defined by ANSI and ASSE among others provides an important road-map for success. Applying visual literacy tools elevates our ability to identify in an objective manner concerns or things that need further evaluation. As we often say at COVE, it is not enough to intellectually know what something is. We must be able to see it as well.