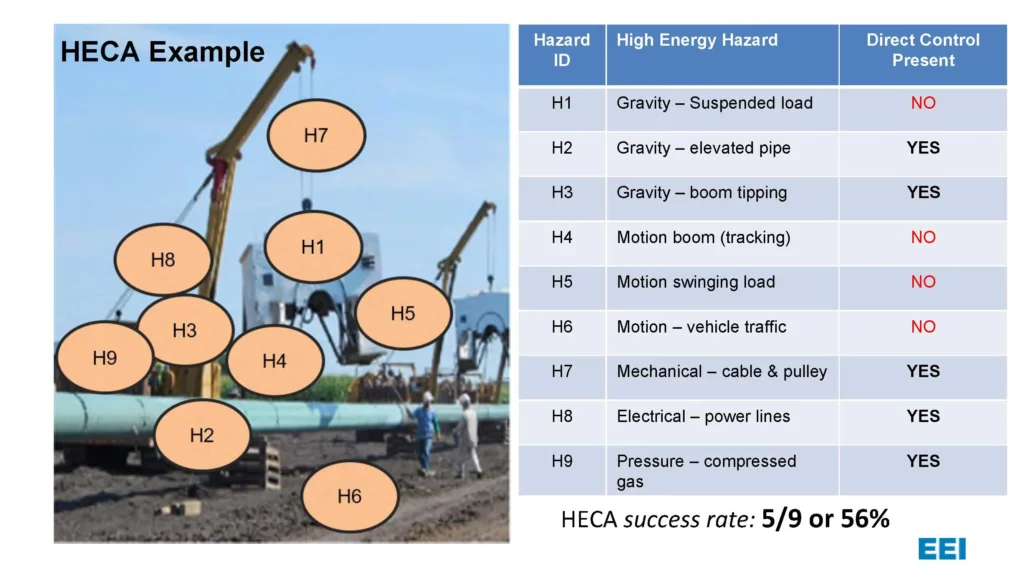

In the decades-long journey to develop leading, proactive indicators to support continuous learning before an incident occurs, a metric involving High Energy Control Assessments (HECA) was described by Todd Gallaher, principal manager, Southern California Edison, and vice chairperson, Edison Electric Institute Occupational Safety and Health Committee, at the recent National Safety Council’s The Future of EHS 2023 conference.

“When we visit a site, what proportion of high-energy hazards have a corresponding direct control?” asked Gallaher in his presentation. Every life-threatening hazard on a site must have a control in place that is targeted at the high energy; installed, verified and used correctly; and is not vulnerable to human error, he explained.

The presentation used one example of a welding cage on a pipeline. Five of nine high-energy hazards had direct controls in place, or an HECA success rate of 56%. Note the emphasis on “success” and not “failure” – which is typically associated with OSHA TRIR measures.

High-Energy Control Assessments can be used by organizations to set goals for incremental improvements, benchmarking, focused planning to mitigate hazards, and focused crew discussions about adequate and inadequate controls before work starts, Gallaher explained. Discussions focus on what specific controls are missing – either not present, not targeted, not used correctly, or not immune to error. Daily discussions raise the success rate (percentage) of direct controls that are in place and reduce the rate of at-risk exposures.

Hazard identification is the starting point

Visual literacy hazard identification, assessment and mitigation training can improve the first three steps of a hazardous energy control program – 1) information gathering; 2) task analysis: and 3) hazard and risk analysis. High-energy hazards must be identified, tasks with the potential to release potentially dangerous high-energy need to be analyzed, and the threat and exposure level to workers associated with each hazard should be identified and analyzed.

Visual Literacy uses elements of art education to deconstruct work condition contexts to uncover obvious and hidden hazards and asks three essential questions:

- What do you see?

- What does it mean?

- What do you do about it?

The application of Visual Literacy hazard recognition and assessment to high-energy hazard safety, specifically in the utility industry, can help workers and supervisors “see better.” In one study reported by the Energy Wheel Review of the Art and Science of Energy-Based Hazard Recognition and cited by Safety Function, workers could identify only 45% of safety hazards on their own..

Visual literacy processes visual information more efficiently by having workers slow down their pace, even briefly, to look, observe and truly see hazards. Workers describe and interpret the hazard’s meaning or potential. They analyze the risk. And communicate a control strategy. This methodology can be applied In the utility industry (and other industries) where energy sources (which are not hazards themselves) can create hazards. Well-known energy sources are gravity, motion, temperature, mechanical, electrical, pressure, sound, radiation, biological and chemical. These ten sources are represented on the famous Energy Wheel, believed to have been created originally by the Chevron Corporation.

Visual Literacy training can focus workers on hazards created by gravity (a suspended load, a fall from height); motion (a swing load, vehicle traffic); mechanical (cables and pulleys, rotating machinery); electrical (power lines, wires, power tools); sound (heavy machinery, pile driving, power tools); pressure (pneumatic tires; piping systems, hydraulic lines); temperature (weather, hot work, torches and sparks, sudden pressure changes, steam); chemical (less obvious hazards that make them easy for workers to miss); radiation (welding, sun exposure, radioactive waste); and biological (bees, snakes, bears, alligators, restrooms).

Research has shown that workers commonly recognize gravity- and motion-created hazards, perhaps due to their life-threatening risks. But workers have difficulty identifying mechanical, pressure, and chemical created hazards, perhaps because on the face of it these energy-created hazards are less obviously life-threatening and might require a sequence of events or behaviors to create the hazard. Unlike more easily spotted swing cranes or unsecured platforms, chemicals, which are often stored, are commonly encountered and less obvious hazards. Welding, soldering and grinding are commonplace, but all contain significant energy that can be released and cause fires and burns to field staff.

The need for critical thinking

Visual Literacy emphasizes critical thinking to:

- Eliminate blind spots in our seeing caused by cognitive biases;

- Evaluate tasks that might result in at-risk behavior or release of high energy;

- Identify patterns and input to envision potential at-risk scenarios;

- Bring an unbiased, unfiltered openness to observe and deconstruct a work context.

In an example used in Gallaher’s presentation, work on a pipeline called for identifying and assessing multiple immediate or potential hazards: a suspended load, an elevated pipe, a boom tipping, a boom tracking, a swing load, vehicle traffic, mechanical cables and pulleys, uneven work surface, power lines, and compress gas containers.

High-Energy Control Assessments are an innovative metric to give occupational safety a “success” orientation in place of its traditional “failure” perception. HECA puts safety “in control” by preventing harm before it happens, not counting injuries after the fact. The first step toward success and being in direct control of exposures is identifying hazards both obvious (and so familiar they are often missed) and hidden and assessing their degree of risk. Visual Literacy teaches transferrable hazard identification and assessment skills that adapt to the specific dangers of numerous industries to improve safety performance. Contact COVE for more information.